Coronado Historical Association’s new exhibition spotlights local Black history

By Martina Schimitschek

Four years ago, Kevin Ashley wanted to know a little more about the Coronado High School basketball team that won the California Interscholastic Federation Championship in 1956. His son, Kieran, was ready to play the school’s 2020 championship game — the first in years — and Ashley was curious about the previous winning team.

As a history buff, he was piqued by the 1956 photo of the nine-member team with three African Americans. He was surprised at the diversity, which started him down a rabbit hole, uncovering and researching 140 years of African American history in Coronado.

His findings are at the core of “An Island Looks Back: Shedding Light on Coronado’s Hidden African American History,” a new exhibition at the Coronado Historical Association Museum opening tomorrow.

“I’m excited to get this out into the world,” said Vickie Stone, Coronado Historical Association’s curator of collections.

“An Island Looks Back” explores the city’s African American pioneer families; military veterans, including buffalo soldiers and those who fought in the Civil War; and students, who excelled in everything from music to sports. The exhibition also looks at Coronado’s federal housing project, as well as tougher subjects such as racism and housing restrictions. Photos and artifacts, such as a 1940 Green Book, a guide African Americans used to find safe places to stay (a home in Coronado is listed), help tell the story.

“What people won’t expect is that Coronado had this much Black history,” Ashley said.

The first 20 to 30 years after Elisha Babcock, Hampton Story and their business partners bought Coronado in 1885, the island was diverse. “In 1906, more than 10 percent of the population was African American,” Ashley said. His interest in the city’s Black history is personal. He and his family moved to Coronado in 2016 from Kenya. His wife is Black, he is White and his two children have navigated what it means to be biracial.

Many early Black settlers came because they had heard of the need for laborers for a grand hotel to be built in the West. Henderson, a wealthy tobacco-growing county in Kentucky, was just across the Ohio River from Babcock’s hometown of Evansville, Indiana. Word of Hotel del Coronado got around as Babcock looked for investors among the area’s wealthy families.

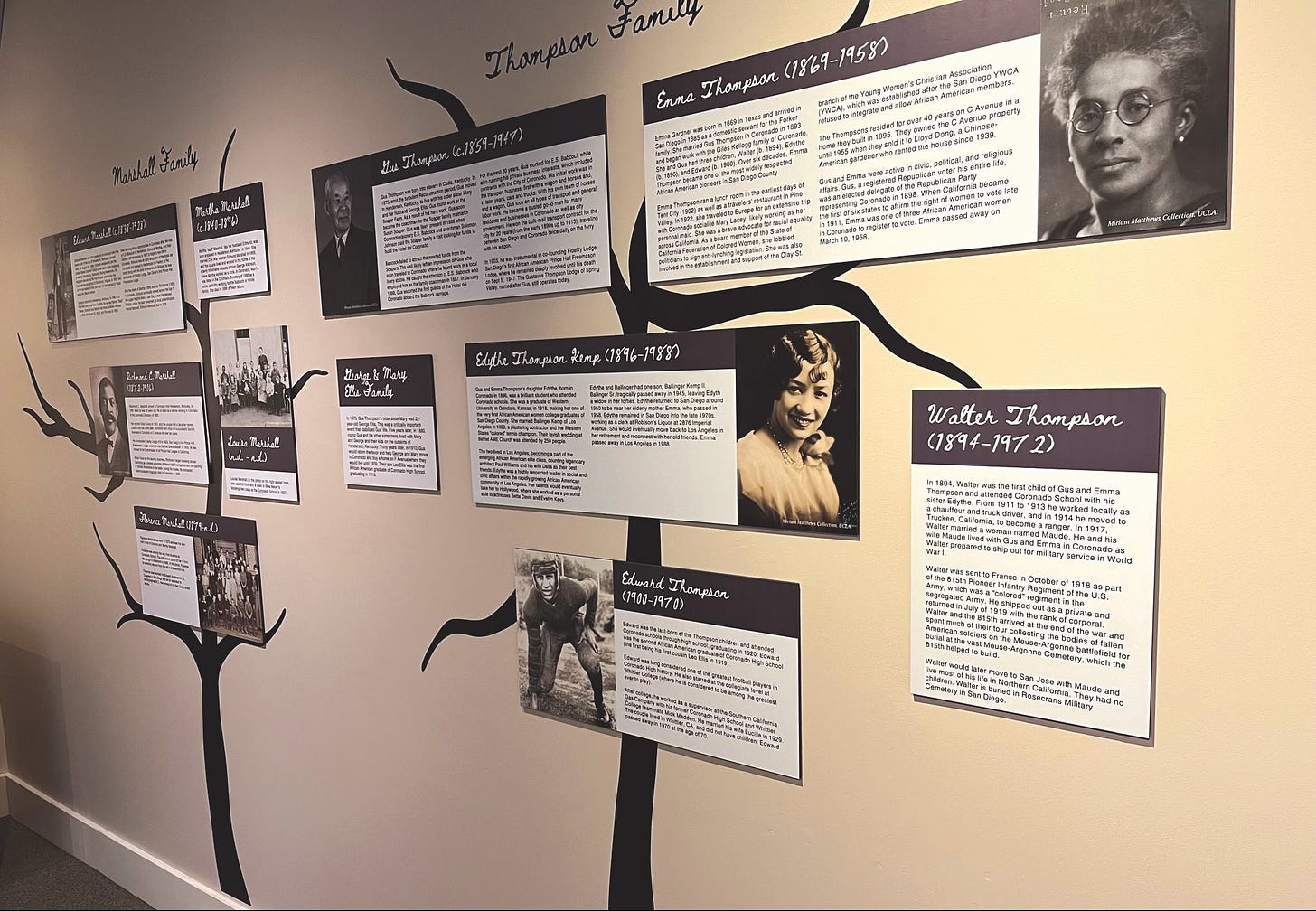

One of the early pioneers was Gus Thompson, who was born into slavery in Cadiz, Kentucky, around 1860. The coachman for the matriarch of one of the wealthiest families in Henderson, he likely heard about the Hotel Del after Babcock visited the family looking for funds.

Thompson moved to Coronado in 1886 to work as a laborer. In 1892, he married Emma Gardner, a staunch advocate for racial equality who became one of the first Black women to vote after California women won the right to vote in 1911.

The Thompsons raised three children on property they owned on C Avenue. They built a house, which still stands today, and a livery stable, one of numerous business ventures between the two. Thompson was the coachman for Babcock and operated a transport business. Emma Thompson ran a lunch counter at Tent City.

Their oldest son served in World War II, their daughter attended college and their youngest son was a star football player at Coronado High School and went on to play at Whittier College.

“The Thompsons were royalty in the Black community,” Ashley said.

Thompson also helped found the Fidelity Lodge, a Prince Hall Freemasonry Lodge, in 1903, which was the first place outside of church where African Americans could gather. Among the co-founders was Edward Marshall, the first African American employee of The Del and the first Black homeowner in Coronado.

Another prominent African American, Edward Anderson, owned a 230-acre hog farm on land that is now Silver Strand State Park.

Up until the 1920s, African Americans had the relative freedom to live anywhere they could afford. But as more Black people left the South to escape Jim Crow, attitudes shifted. It was the beginning of what Ashley described as “the darkest chapter for minorities,” which lasted until World War II. African Americans could no longer buy property as real estate restrictions against minorities were put in place, and racism was rampant as evidenced by the hugely popular blackface minstrel shows.

With the start of World War II and the expansion of the Navy in Coronado, the community became more diverse. The increase in the African American population was due to the federal housing project, which was built in 1944 on the northeast corner of the island. Originally operated by the Navy, the 750 rental units brought in 3,000 residents, including more than 400 African Americans.

But outside of federal housing, African Americans were not welcome as residents.

“I started to realize Coronado is White today because of what Realtors did. It was socially engineered,” Ashley said.

Racial steering, in which real estate agents nationwide, as members of the National Association of Real Estate Boards, were required to discriminate, started in the 1920s, Stone said. That practice was set in place in Coronado by 1927 and expanded during the post-war housing boom. Developments had discriminatory deeds prohibiting African Americans from buying property including neighborhoods with Palmer Bilt homes and the Country Club Estates.

Between 1927 and the late 1980s, only one Black family was able to purchase a home in Coronado, Stone said. Emmett and Fidelia Rogers bought a small home on I Avenue. Most likely, it was the couple’s connection to the White House that allowed them to buy the house. Emmett Rogers’ mother, Maggie Rogers, served as a maid in the White House from 1909 to 1939 and his sister was a seamstress and domestic assistant there from 1931 to 1961. Maggie Rogers served the wives of six presidents including Eleanor Roosevelt, who with her husband, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, were frequent visitors to Coronado.

How these restrictions shaped Coronado is “the most important community story we’re telling,” Stone said. “As a community it’s something worthwhile to discuss.”

But despite the racial restrictions, Coronado schools have always been integrated, with African American students attending as early as 1887. “A lot of schools across America couldn’t say that,” Stone said.

The exhibition also devotes space to African Americans in the post-bridge era, which covers the past 55 years. The housing project was torn down with the construction of the bridge in 1969, and Ashley said his research found that the first Black family to rent an apartment in Coronado wasn’t until 1974. Local Black Lives Matter activism in wake of the death of George Floyd in 2020 is also covered.

“Seeing the stoicism of the community through what’s clearly a never-ending struggle for full equality — the strength and resilience of the African American community is incredible,” Ashley said.

He hopes this exhibition will give people a better understanding of the lives of others and a better appreciation of our common humanity.

“That would be success,” he said.

Martina Schimitschek is editor and co-founder of Coronado 365 Magazine.